Location

We are located on the 9th floor of the Armour Academic Center, in what was previously METC space. You can contact us any time by emailing CTEI@rush.edu.

Mission

The Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation, under the division of Academic Affairs, supports and enhances teaching at Rush University by promoting teaching excellence and innovation, and student engagement throughout all learning experiences at the university. This is accomplished through faculty education and consultation, program consultation on curricular and programmatic enhancement, and support of the university’s mission regarding strategic teaching initiatives.

What do we do?

Provide support for all teaching modalities

The center provides workshops on various subjects that provide new skills or enhance current skills related to teaching, and one-on-one support for faculty to improve their face-to-face, blended, or online courses. Additionally, the center offers regular training for online teaching through the Online Teaching & Course Design class (OTCD) at least 3 times per year in Fall, Spring, and Summer.

Assist colleges and programs

Center staff members provide services for colleges and/or programs that are considering changes to their curriculum or pedagogical practices. Those services can include support for new teaching modalities or assistance with curriculum development, mapping and alignment of content with objectives and assessments. The center assists colleges and/or programs with student learning outcomes and assessments by using student performance data to make decisions on curricular or pedagogical change to improve outcomes and assessment performance.

The hub of innovation

CTEI is a department focused on the use of technologies to enhance teaching and course experiences. The staff members provide primary faculty support of the university’s learning management system (LMS), as well as initiate and support educational technologies used in courses and programs. CTEI staff members regularly explore new and more innovative ways of teaching and remain current on the most up-to-date advancements in the educational technology landscape.

Ensure quality online learning experiences

The center works with faculty members to ensure their online courses meet or exceed Rush University standards for online course design and online teaching. Center staff members work with colleges to provide support as requested, by college administrators and work in partnership with the units to ensure online courses are of the highest quality possible. The center is also involved in Quality Matters reviews of certain courses.

Are you Rush University Faculty? If so, find out how our faculty is involved in what we do and how you might be able to get involved as well.

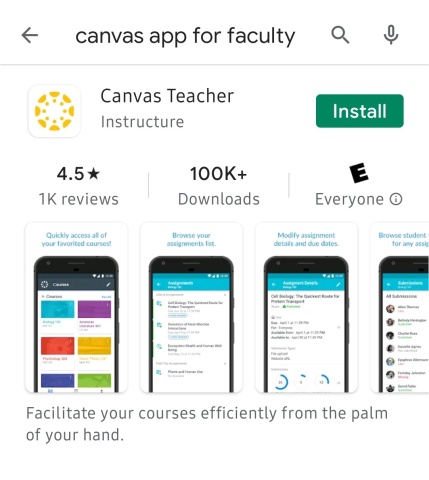

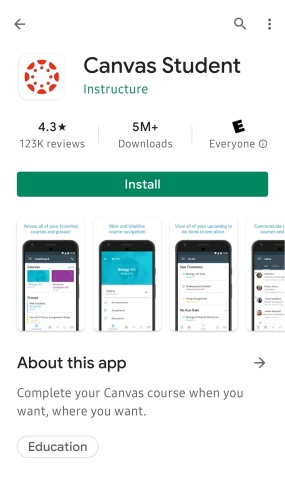

As of Fall 2022, all Rush University College of Health Sciences, College of Nursing and Graduate College courses are utilizing Canvas for course management.

Visit our Canvas page for information regarding the transition and training opportunities, Canvas Learning Management System Updates.

Interested in learning new teaching skills or technologies? See what we offer and how to participate.

Interested in the learning technologies offered at Rush University for our faculty? Check this link regularly for updates or to request a technology.

In this section, you will find a variety of helpful resources, such as Canvas tutorials, information about teaching strategies, dealing with student issues, educational research, and much more! Visit often as this will be updated regularly.

Within this link you will find the Rush University standards, helpful resources for teaching blended and online, and information about training offered for online and blended teaching.

Quick Links

Rush University syllabus template for Canvas (updated 11/23/21)

Rush University College of Nursing Syllabus for Canvas (updated 11/23/21)

- Syllabi require a rush.edu email to access

- Download the Syllabus template to edit

Helpful Information

Canvas Information for Students

For faculty members: Who do I contact for what? Should it be an instructional designer, 3-clas, or an instructional technologist? Find out on this handy, one-page handout

CTEI YouTube Channel - find workshops and more!

Online Standards

Rush University Standards for Online Course Design

Rush University Standards for Online Teaching

Self-evaluation for online course design

Self-evaluation for online teaching

Our friendly Instructional Designers are available to get you ready for Canvas. Please reach out to any one of them for questions or assistance with Canvas.

Director

Angela_Solic@rush.edu

(312) 563-3740

Instructional Designer

Lynette_Washington@rush.edu

(312) 942-3152

Instructional Designer

Branka_Manojlovic@rush.edu

(312) 563-0587

Instructional Designer

Margaret_Checchi@rush.edu

(312) 563-0917

Instructional Designer

Laura_Smith@rush.edu

Phone TBD

Instructional Designer

Emily_M_Rush@rush.edu

Phone TBD

Instructional Technologist

Daniel_Martin@rush.edu

Phone TBD